The timeless cliche ‘work smarter, not harder’ takes on a new meaning through the revelation of Morten Hansen’s quest to be great at work. In his research of 5,000 managers and employees, Hansen uncovers patterns of unconventional wisdom that enable high performers - Let’s explore three key elements.

We have all heard it before. If you google ‘work smarter, not harder’, you will surely get a variety of memes depicting efficiency via the use of the right tools or systems. The general idea is that having the right tool, for instance wheels on a carriage, will get you further faster (with less effort).

In the office, instead of wheels, we use our computers, email, chat, meetings and project management systems. We are wired to our devices and our ever-increasing ‘to-do’ list. However, even with the right tools, the right intention and many, many hours of work, people may still underperform. So what sets high-performers apart? How is it that some people seem to work less and achieve more quality work?

Curious consultant

Some years ago, a driven management consultant by the name of Morten Hansen was working intensely on merger & acquisitions projects, putting in 90-100 hours per week. Yet he noticed that other colleagues worked less and produced better work than his own. How is it possible that a colleague that works 50 hours per week, can perform better than someone putting in nearly double the effort?

In one of our previous podcast series at Oslo Business Forum, Hansen shares that he felt puzzled, even hurt. “Her slides were crisper and more synched than mine, her analysis was better, more in-depth, and I thought I did well. I did, but she did even better,” says Hansen. He never really fingered out what this colleague did. But he embarked in a 5-year study of 5,000 managers and employees in corporate America and found something even better.

Hansen’s main conclusion is that the top performers, regardless of seniority or industry, work differently. “We have been using this ‘work smart, not hard’ lingo for decades. But if you really look at that slogan, it’s an empty slogan. What does that mean to ‘work smart’?” says Hansen.

In his book ‘Great at Work’, a Wall Street Journal Bestseller, Hansen maps out seven main factors that enable top performance - here are three key takeaways.

Do less, then obsess

The general idea is that by choosing a tiny set of priorities, and at the same time, making an intense effort in these areas, produces quality work. Here are a couple of examples to further illustrate the idea.

It is said that the late Steve Jobs would often challenge Jony Ive, the former Chief Design Officer at Apple; asking How many projects have you said ‘no’ to last week? It is easy to say ‘no’ to projects that don’t serve you. But what about projects that with every bone in your body, you want to do? Herein is the challenge.

“You’re already working on good ideas, but there are only so many you can do,” says Hansen. He explains that this is particularly challenging when teams are spread out too thin relatively to the resources.

Hansen also makes a reference to the film “Jiro Dreams of Sushi,” a story of a 90-year old Japanese chef who became the first person to receive 3 Michelin Stars for sushi. Jiro Ono’s restaurant is a modest tiny establishment in a subway station in Tokyo. What is remarkable about his cuisine is that ever since World War Two, Jiro has intensely focused on the same menu of about 20 pieces.

“If you’re picky in what you do, then you can go all in and make those 20 pieces the best in the world,” says Hansen. “But you can’t just choose 20 pieces of sushi, and apply average effort.

You have to have the obsession, and it sounds harsh, but it is obsessive.” Jiro’s journey to perfection still continues and Japan has declared him a national treasure.

Bottom line: focus on what matters the most and applying intense effort.

Creating (actual) value

Don’t count on metrics alone. Sometimes we make wrong decisions based on irrelevant facts. “We are goal oriented, but we are not always asking if those goals are creating the most value,” says Hansen. “We need to be more value oriented, than productivity oriented.”

For example, Hansen makes a reference to a tech company in Silicon Valley that was measuring how good they ship things out on time. The person in charge was achieving his goal 99% of the time. Praise and promotions were surely given. But then a different question was asked: Did customers receive the shipment on time? Surprisingly, one third of the time shipments arrived too late, which of course, indicates a poor performance.

In a different industry for example, hospitals in the US are not necessarily tracking internal measures like the number of patients treated, nor number of beds, nor number of nights spent in the hospital. While all these are relevant measures for productivity and quality assurance, the real (customer) value is in whether the patient received the right diagnosis and the correct treatment. By contrast, there is a recent story on The Financial Times, citing that a “London primary healthcare organisation set 30,000 KPIs.” The article explains that “from public health to business, clumsy target-setting can distort behaviour and undermine good outcomes.”

Bottom line: Set clarity by defining what creates the most value; and then track your progress.

Fight, then unite

Have you ever seen that coffee mug that reads “I just survived another meeting that should have been an email”? Meetings are a core element of work, yet there is a love/hate relationship to the concept. In his research, Hansen uncovers how top performers lead meetings and teams. The main outcome should not be alignment in itself, rather meetings should be a platform to fight and then unite.

A great meeting should consist of three things including the right people, a healthy debate, and then uniting on the decisions made.

Diversity and opposing opinions in meetings are essential to thrive in the future. “Just imagine you have people who are exactly the same - same background, same information, same gender, in a room debating. That is a very narrow debate,” says Hansen. “You need a diversity of perspectives, if you want great ideas and great decisions.”

Facilitating the meeting may be easier said than done. Hansen encourages leaders to practice their skills on a regular basis. To properly prepare for a debate, the leader needs to be able to provide a safe environment for sharing ideas, as well as balancing an individual's share of voice during the meeting. Start by asking open-ended questions. In addition, the leader needs to ask participants to take the devil advocate perspective, ask somebody to pick up the minority point of view, and ask the team to challenge the assumptions. These are all specific behaviours that a leader can practice which will constitute a healthy debate.

The principle of uniting after the debate is essential. There is no sense of having a healthy debate and then no follow through on the decisions. Or even worse, if people try to appeal the decisions to some other senior person who was not in the meeting.

Bottom line: Develop better ideas through diverse perspectives and structured debate. Then unite the team with clear decisions to build progress.

Ultimately, Hansen's research shows that the top performers didn’t put in 90 hours - they put in 50. It was not how much they worked, rather how they work.

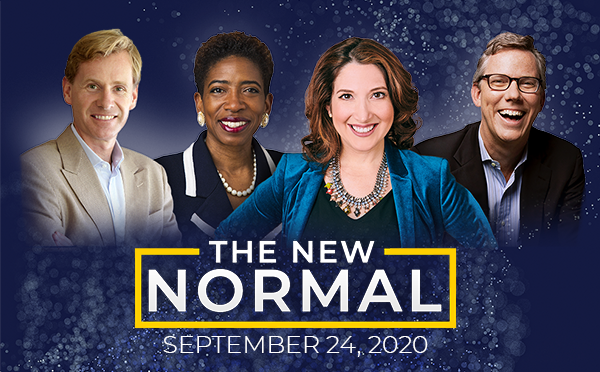

Morten Hansen will be joining the online conference 'The New Normal' the 24th of September. Want to join? There are two ways to join:

A management professor at University of California, Berkeley. He is the coauthor (with Jim Collins) of the New York Times bestseller 'Great by Choice' and the author of the highly acclaimed 'Collaboration and Great at Work.' Formerly a professor at Harvard Business School and INSEAD, professor Hansen holds a PhD from Stanford Business School.